A First and Last Experience of Fire

We’d had a good year and the grass was abundant and high. This summer of course had been scorching hot so after early rains grass was dry and wheat coloured but full of nutriment and goodness. Storm clouds were about so as usual when there was danger of lightning and fires the horses had been brought in at lunchtime and shut in the horseyard in case of sudden need, and the truck loaded up with firefighting gear.

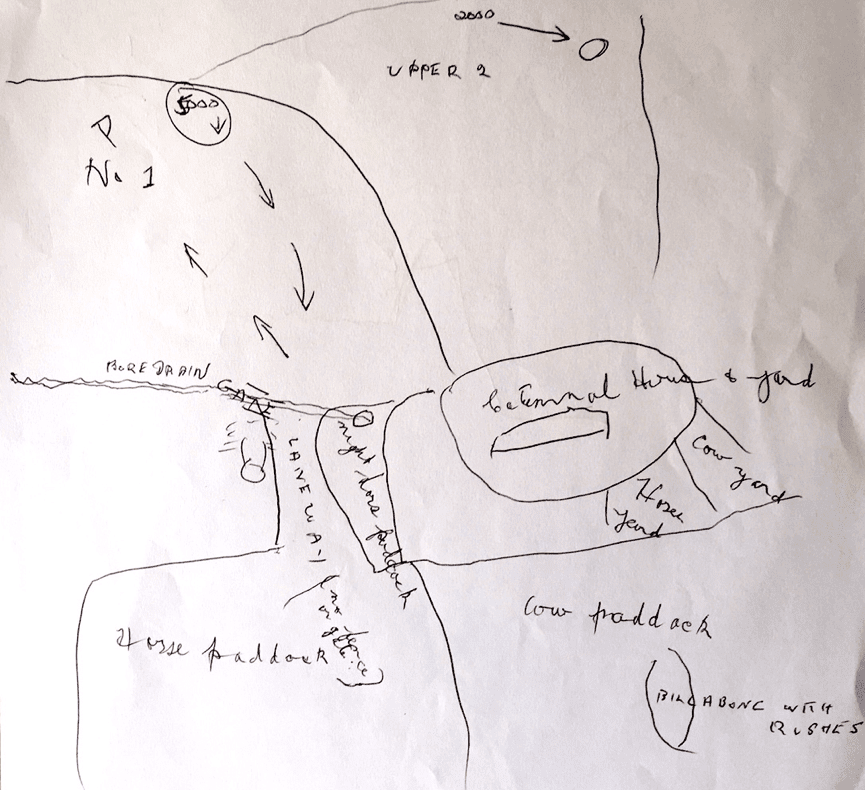

Four or so thousand sheep were mustered on the property to be put into number 1 which was the nearest to the shearing shed as it was the day before shearing. A day’s supply of sheep to be shorn were to be taken to the shearing shed as required. 2,000 were in reserve in number 2 – (upper 2).

They were the worst kind of storms that day, Full of fireworks but little rain, so predictably, about 2pm there were a few fires started. There was one very active one with huge clouds of black smoke on our northern neighbours’ property Cairn Hope. My father and two men set off to help fight it. There was a good wind from the west so the fire was moving steadily to the east. At that direction it would not reach Catumnal. It burned on for hours until it was many miles long across our northern boundary. Then the wind turned from its previous direction and blew in from the north. This headed the length of the whole fire down onto Catumnal. It was very frightening. There were no men on the place and we could see that they could not get back because the whole area of the road would now be ablaze. This left me, Mum, Irene the lady help, and Mr Bingley, a very large half crippled carpenter (doing some repairs on the house) on the place to deal with getting the sheep out of the way of the fire. I knew I was the only one who could do anything about it and I was really panicky. I knew that I had to spend sometime sitting down and making of foolproof plan. I forced myself to do this, calm down and think clearly. I surmised that the homestead would be safe. On the west was the night paddock closely cropped, adjoining the eaten out laneway; on the north was a long stretch of lawn and then a large tennis court adjoining a ploughed orchard. On the east was the front entrance gate with a large bare area inside it adjoining the house garden and the south had bare ground as well with shale paths leading to sheds and horse and cow yards. Yes it should be protected. Finally I came up with a plan. I asked Irene to go down to the windmill on the house dam and leave it turned on to keep plenty of water in the overhead tank to defend the house. I asked Bingley to put all the hoses on the taps at various points of the house and asked Mum to stand guard on one of them when the fire came close. The dogs were to be tied up in the empty ungrassed cow yard, and then I told everyone I was going up as far as I could in number 1 paddock, the closest to the fire, to bring the sheep down to the bore drain area which was eaten out. The bore drain flowed from west to east across number 1. It ended in the house dam. I asked Irene two open the gate into the laneway when she saw me coming and then I’d put the sheep through it. I asked her to then prevent the sheep getting out the only unfenced side of the laneway with the help of the dogs. A tall order, but our only hope. The laneway was cut into number 1 to provide water from the bore drain for the horses in the large horse paddock. The laneway was about 100 yards long and 50 yards wide and fenced on three sides, and with gates to allow the tractor and (word illegible) through.

Most of the sheep had just been put in number 1 as we were soon to start shearing and that paddock was handiest. I took a horse, the blue pony again, saddled it and made fast time up towards the back of the paddock. Here I had my first piece of luck, the sheep were already on the move down to have their afternoon drink. I rode up behind them and hurried them down. They must have sensed the fire and broke into a run. I did not go further to look for stragglers. They would have to look after themselves and I could see that I had the main mob running down to water. I also had to get up to Top 2 before the fire to put a reserve of sheep there onto a dam.

It took a long time but finally the number 1 sheep were safely in the laneway. I left Irene the blue pony and the dogs and left her on guard to keep the sheep in place. Then I took a fresh horse and set off again at speed to the top of top 2 up near the fire. I knew the sheep would be resting from the heat up there under the trees. My second piece of luck was that they all seemed to be there–just a couple of hundred yards from a big earth dam with high walls and eaten-out grass around it. I started them off towards the dam. They didn’t resist and we moved off slowly. It was then that I heard a noise approaching. It scared me because I had no idea what it was. I’d never heard the like before. It grew louder and even horse began to be spooked. Then its source became obvious. Everything that could fly was moving in front of a wall of smoke–grasshoppers mainly, birds and every kind of insect. The whirring of their wings made quite a din. Then we were enveloped in yellow smoke. The light of the declining sun had turned the smoke yellow and it made everything else yellow – my horse, the grass, the sheep, the trees. It was a weird feeling. I pressed the sheep on knowing the flames weren’t far behind. They went on up the dam wall, down the other side and towards the water. After a short melee there they sensed the fire and wanted to go on. Old Dick and I had a busy time rounding them up and keeping them in safety on the walls and around the water. Finally they settled down (more luck) and some drank. Then the fire at last came sweeping down each side of us. We felt the heat and my sweaty brown horse dried to a rather dirty white colour, but the flames did not come too close because of lack of grass. I had a wonderful view from the top of the bank of the anatomy of a fire in Mitchell grass. Where the grass was thickest the fire burned fiercest. It eventually whirled itself into a revolving wheel of flame, then exploded with a loud bang into a long tongue and unrolled (like a butterflies tongue) at explosive speed to about 20 yards ahead. Nothing in its path could have got out of the way. These tongues eventually burned towards each other and became one fire, then their hottest spots repeated the process, went into a fast moving vertical, stationary swirling ball round and round until they exploded into a tongue and shot forward again.

The sheep stayed still. They were hemmed in by flames anyway and couldn’t go anywhere. I looked over towards the homestead and it was not a reassuring view. How were they getting on I wondered? The ridges hid the house from view but the top of those ridges were in dire straits. High flames whirled their way forward. There was an even fiercer fire over there than where I was. I could only feel great anxiety.

The night came and with it the wind dropped. The night air grew damp and the fire began to sputter and decrease.

Our bushfires were not like the dreadful crown fires of the forest country. When the sun was hot and the fuel supply available and the wind behind them they burnt fiercely. Deprived of all this they soon faded and died out. It was so with this fire. Once the ground and stubble cooled down I could let the sheep go and ride home.

Then there came a sight I had not expected to see: Irene on the blue pony. She came up from the south on some unburnt country. I was quite shocked.

Irene was what you could you call a ‘goer’. My mother had received a letter from Irene’s mother asking if she could have her asthmatic daughter for a year or so to see if the dry country air would do her any good. The two women had been known to each other years ago at Bingera so Mum acquiesced and Irene came to stay with us and ‘help’. She was just as interested in outside work as inside so she insisted on learning to ride and muster in the sheep yards. This was wonderful for Dad especially as she wanted to learn to milk cows which he loathed doing. So she was a great hit. She’d learned the geography of the place and had been able to find me and of course she didn’t know the danger of riding across the front of an active bushfire. I was really shocked but didn’t say so. I enquired about the sheep she’d been minding. “Oh they are OK. Mr Bingley is looking after them”. “Mr Bingley, what about his sore feet?” “Oh, he’s taken down a stool to sit on. Enid your mother was so beside herself about you that I felt I had to come”.

Well that was something I hadn’t thought about and of course Mum had been worried. I’d been worried about her and she would have seen the same flames between us. Irene went on to say that Mum and the homestead were okay when she left and Mr Bingley had the dogs with him so the sheep should be okay.

I pondered on this for awhile and somehow the mental picture of the enormous Mr Bingley sitting on a small stool with 5,000 resentful sheep glaring at him and dogs ready to raise whoopee began to look very funny. I didn’t know Mr Bingley’s qualifications as a dog handler. I smiled, then laughed and laughed– and laughed. It must have been the release of tension. Anyway I felt better.

The stars were making a slight illumination and one picture that has never faded is of the two of us sitting on our horses on that dam wall with 2000 sheep below us, resting near the water, some chewing the cud, and the pink light from the dying fire glowing in the sky and reflected onto the surface of the dam. It was a beautiful scene and a peaceful one that the trees on the ridge framed. Where sheep camp there is little grass so the trees had remained unburnt. Strange how some particular images remain. I can still see all the details.

As things cooled down we picked our way over to the road and made for home. It was a long distance away but we at last reached the ridge hiding our view of the homestead. Then we saw two things. One was the lights of a car coming up the ridge towards us and the other was the sight of rectangles of flame – the roof, walls and floors of Catumnal burning. I looked and looked. Irene said, “But it can’t be – it was alright when I left”.

I felt desperately ill. I couldn’t believe it. This was too much and my brain wouldn’t accept it. I thought in my desperation that if I looked away it would be gone when I looked back – that I’d see my mothers face and it would all have been a bad dream. I looked up at the sky but that didn’t help because the stars were all moving around in a circle meeting and multiplying and becoming one again. I was very giddy and clutched the pommel.

At this stage we were caught in the headlights of the advancing truck. I must have looked ghastly because Harry Thorpe jumped over, grabbed my stirrup, and said “Enid, what’s the matter? What’s wrong?” I couldn’t reply but Irene pointed. Harry looked back and understood in an instant. “Now look girls, that’s not Catumnal, that’s the rubbish heap burning those big packing cases. The fire got them–cleaned up your whole rubbish heap for you. We’ve just passed it”. I heard every word but was quite unable to take it in. I had a picture fixed in my mind and it wouldn’t shift – terrible red flames burning my home.

Harry and gang helped me off the horse and set me on the running board of the truck. Someone produce some terrible potion and I took one swallow. It was enough to startle me back to sanity though. I gradually took in the news and gradually began to feel great. Yes of course it was Motony Joe’s packing cases burning. Motony Joe the well sinker had arrived with his huge new machinery in packing cases and had left them side-by-side on the rubbish heap about 100 yards from the house.

Soon cups of tea were produced from thermoses and lots of sugar and the atmosphere took on the air of a party. Witticisms flew thick and fast, and the talk was mainly of “Westy’s luck”. I wasn’t sure I could agree with this but was told “of course it was so – hadn’t he won his first bit of country at the first try, and the last time he got burnt out the sheep were saved and 3 inches of rain fell that night. Hadn’t he taken some old nag out of the paddock and won the Tower Hill cup with it? And look at today’s luck. He’s not even on the property and someone saves all his sheep for him!”

And so it went on. It was all very pleasant but Mum was home and worried out of her wits so soon the party broke up. The boys wanted to ride our horses home and let us travel in the truck but somehow neither of us wanted that. Anyway they had a long drive home and were blackened with smoke and soot and dust from fighting their own fire, so after asking them to call in and see Mum on the way to tell her we were okay we went to mount our horses. To my extreme embarrassment I could not get up on my big horse. I just didn’t have the spring! This occasioned more witticisms. “It’s all your fault Wettenhall–you and your OP rum. Look at the state the poor girl’s in–she can’t even get on her horse. You stand over there to catch her and I’ll get her up this side–but she’s sure to fall off the other side”. But at last I was up, we waved a cheerful goodbye, and they were off.

We had last arrived home, released the horses and gave them a feed, reassured Mum and had a debriefing session before Dad and the men arrived home. Mum had done her part by hosing out a burning post holding up the wire netting on the tennis court. The flames must have come close to the house and poor Mum would have been terrified. Irene had already left to look for me. Mr Bingley had done well too. He had had experience of handling dogs in the past and been able to keep the sheep in the laneway for as long as necessary, and they were now feeding quietly in the big horse paddock. Good old Bingley. I was grateful to him.

We could now have something to eat and go to bed – about midnight. If the others were like me they wouldn’t have much peaceful sleep. They’d have spent a good part of the night seeing fire and smoke and hearing the roar of flames.

It did rain a few days later – right in the middle of shearing of course – but one never begrudges rain in that country.